Holidays can often be life-changing. For Vladislav Doronin, the international property developer, one certainly was. The first time he walked into an Aman hotel – Amanpuri, in Phuket, Thailand, in 1990 – he found that “it was not like anywhere else I’d stayed . . . It felt like a home, but the most beautiful home. The staff were incredible, no one bothered you. I was really impressed.”

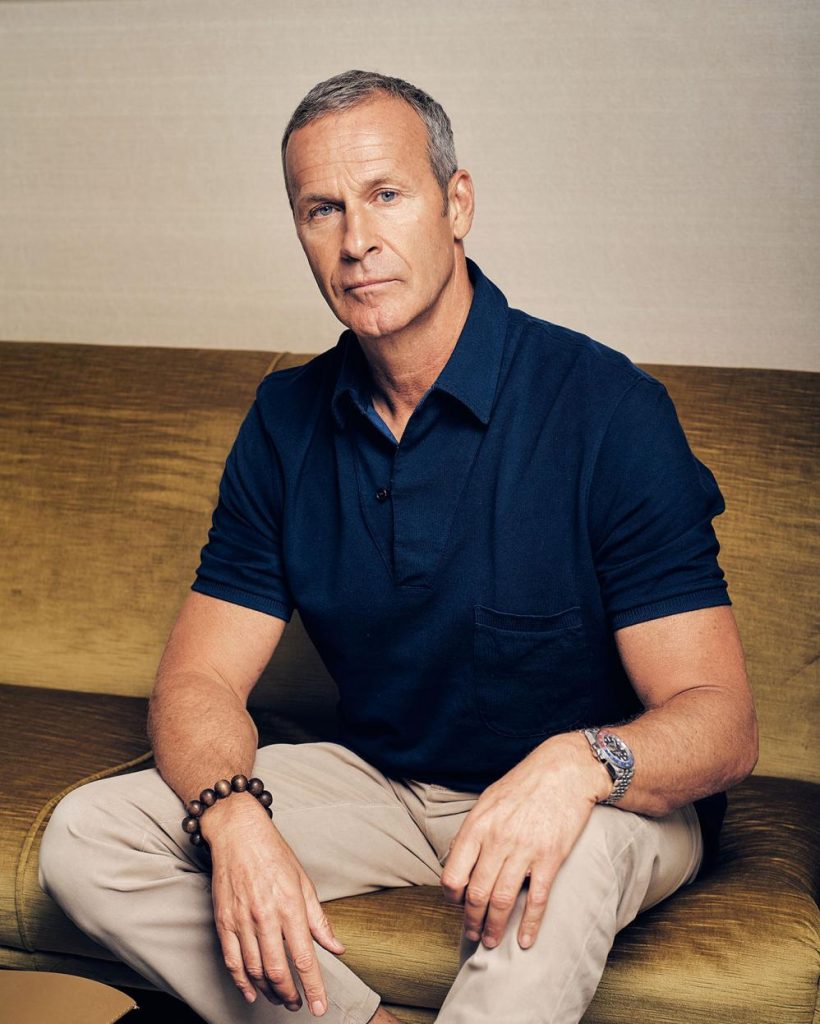

Regular “Amanjunkies” might have just booked another holiday. Doronin, 57, did something different. In 2014 he bought the 26 properties, founded by Adrian Zecha, for a reported $358 million.

Five years on, the Aman brand is stronger than ever, with 32 hotels in 21 countries, from the beachside Amankila in Bali to the high-rise Aman Tokyo. On November 1 Doronin opened his latest hotel, 28 rooms in a 32-hectare hillside garden in Kyoto, Japan, and there will be four more by the end of 2023: in New York, Mexico, Saudi Arabia and Bangkok. His property company, OKO Group, is building several buildings in Miami, one with 47 floors, another a 57-floor skyscraper. The New York Aman, which opens next year, will be the most expensive hotel built in the city, he says. “When I say expensive, I really mean it,” says the billionaire when we meet at his understated, Scandi-style office in Mayfair. “It’s been really difficult, and cost me a lot, which is probably why no one else builds hotels in New York.”

The Crown Building, built in 1921 on the corner of 57th Street and Fifth Avenue, is one of the four architectural classics of the New York skyline, alongside the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building and the Rockefeller Center. Said to have cost $560 million in total for floors 4 to 24 and leases, the Aman project includes not only a hotel, but also 20 apartments, costing from $8,000 a square foot. Half of the apartments have already been sold, including the 15,000-sq-ft, five-storey penthouse, with its indoor and terrace swimming pools, for a reputed $180 million.

“People say it’s expensive, but expensive is relative,” he says. “In New York people say everything is a ‘luxury apartment’, even if there are 100 in a building. In mine there are just 20, so you’ll feel like you’re living in a house. Plus, you’ll have all the services of the hotel, the biggest spa in the city – 22,000 sq ft, run like a private club – and interiors by Jean-Michel Gathy.”

Aesthetics are important to Doronin, whether that’s in his choice of architects (mostly international superstars) or the furniture in his homes: Gio Ponti, Jean Prouvé, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe are favoured designers. His sensibility, he says, is largely thanks to his mother, who practised ballet and regularly took him to galleries in St Petersburg. She also encouraged him to take his camera on to the streets to capture small moments of beauty. “I took photographs of everything, everywhere I went,” he says, “especially buildings that were interesting, odd details. It’s funny, I still have tonnes of them.”

He learnt about hard work in Geneva. In 1985, aged 22, he left Russia with a reputed $250 in his pocket (“the maximum you were allowed to take”) and got a job with Marc Rich, the commodities broker. “I was always the last guy who left the office. I stayed very late,” Doronin says. “I learnt and learnt and learnt . . . I had to. It was a small salary, and [only] if you did well, you got a bonus.”

Which he clearly did. Eight years later, when he returned to Moscow and founded the property development Capital Group, his first project was to build the new Russian headquarters for IBM. Under his leadership it constructed more than 70 significant buildings in the country, including the OKO complex; at 354m its South Tower is higher than the Shard in London.

Today Doronin is estimated to be worth about $1.6 billion. He has homes in London, Ibiza, Moscow, Miami and New York, and an extensive collection of Russian and international artworks. This ranges from early life drawings by El Lissitzky and Malevich (“I couldn’t afford paintings at that time, so I bought drawings”) to a growing number of contemporary American works by Edward Ruscha, Jeff Koons and Dennis Hopper, a friend whose personal photographs Doronin bought near the end of the actor-turned-photographer’s life.

He also has an impressive array of toys, from superyachts to jets. For fun he flies a helicopter. To keep fit he kitesurfs with a personal trainer – ideally from his Aman in the Philippines, where the beaches are “perfect: three kilometres of white sand, on one side protected and on the other side windy”. He has a private chef who prepares mostly plant-based food, as well as a trainer who works with him daily and is an expert in Chinese martial arts, shiatsu, herbal medicine and acupuncture. “Sometimes he gives me treatment with needles on my plane, which helps with jet lag,” Doronin says. “Or he uses my Tibetan singing bowls.”

The people most essential to his wellbeing are monks. “After I met Chinese and Tibetan monks, I started to live life differently. I met one in Nepal, one in Canada, one in Bhutan, one in New York. I try to combine what they teach me with my life. I don’t want to be a monk; I have a social life, I have a family. But I got a lot of strength from them and am very happy I met them. It changed me.”

They showed him “how to recharge my battery, find peace and clear my brain”, and taught him about the therapeutic value of nature – in Bhutan in particular. “It is such a spiritual place for me. All that fresh air and temples and hikes, and the combination of vegetation and mountains. I did my best hiking anywhere in Gangtey. It was raining, but it was fantastic. There were all of these wild flowers – thousands of rhododendrons. I would fly across the world just to do that hike.” Last year he spent 780 hours on his plane, a Gulfstream G650. While it’s “a nice plane, very nice”, it’s not something he considers a luxury. “I use it like a limo. It’s a way for me to get places faster. So I can go to Nepal and Bhutan. I can work on it, watch the news, talk on WhatsApp. And sleep – it has a bed.” And a shower? “No. Maybe in the next one I’ll get a shower.”

His boats are more his idea of fun, “because I’m a Scorpio, a water sign”. There is one, “slightly less than 100m”, that he uses for holidays; a Wider 42 for watersports “because it opens at the sides”; an American MTI speedboat, “which goes about 80 knots an hour, to get from Miami to the Bahamas in, like, 45 minutes”. Yet because he’s so busy he rarely gets to go on them.

“Last year I had to cancel three times,” he says, shaking his head. “One day I will go around the world with my family. See places like the South Pole. Or before that, the North Pole definitely – which is why I’m constructing an expedition boat . . . I just have to find time.” His biggest extravagance, he says, was probably his Russian home: the only private residence designed by Zaha Hadid. Towering above the forests outside Moscow, the organic, Starship Enterprise-style Capital Hill Residence structure is said to have cost $140 million, and was drawn by the architect on the back of a napkin over lunch at the Wolseley.

Although he considers London, New York and Miami his homes, rather than Moscow, he wouldn’t want to sell the Hadid-designed house, he says, his blue eyes clouding over for a moment. “It’s the only one she built, so it’s special . . . We were meant to be meeting for dinner the week after [she died]. It was so sad, because she was so talented.” While he might go back to Moscow for a week every now and then, to stay in the house or go to the white nights balls, he adds: “I haven’t had a Russian passport since 1986. I have to queue for a visitor visa like you . . .”

And with that he packs me off, with the gift of an Amanjunkie T-shirt, from his new fitness range, and an Aman body moisturiser, launched last year, in a sculptural wooden bottle designed by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma.

Read the full article: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/vladislav-doronin-interview-on-his-aman-hotels-and-how-monks-help-him-to-relax-mxpsljznj